An outpour of tributes followed Zaha Hadid’s sudden passing last year, attempting to fill the void that the 65-year-old architect had left in the field. Many dubbed her fearless, visionary, iconic, larger than life, groundbreaking, and highly experimental. To others she was a diva, a caffeine-loving, chain-smoking ‘Queen of the Curve;’ a rock star; designer of spectacles; individual of great courage, conviction, and tenacity; the greatest female architect of her time with a disregard for dull functionality and penchant for experimentation, who built the unbuildable. Her mentor Rem Koolhaas once called her “a planet in her own inimitable orbit.”

Needless to say, Hadid left an imprint of her style and flair on the architecture industry not to mention urban landscapes around the world.

Some of her most iconic buildings include Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP) in Seoul, the London Aquatics Center built for the 2012 Summer Olympics, Galaxy Soho in Beijing, the Jockey Club Innovation Tower in Hong Kong, and one of her first pieces that put her on the map, the Vitra Fire Station in Germany.

She has been celebrated as the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize – the Nobel Prize equivalent in architecture – a recipient of the UK’s most prestigious architecture award, the RIBA Stirling Prize, and the first woman to be awarded RIBA’s royal gold medal in her own right.

Celebrating Hadid’s Spirit of Innovation

Discussing her legacy just a year and a half after her death may be considered premature by some. Many of her projects are in fact still under construction. But, no one is as uniquely qualified to do so as Patrik Schumacher, the principal at Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), who played an instrumental role as Hadid’s collaborative partner for 28 years.

On September 4 in Seoul, Schumacher delivered a keynote speech at the triennial UIA world congress, looking back at Hadid’s legacy and what lies ahead for the architecture and design firm she left behind.

Hadid’s works are often described as undulating, swooping, curved, futuristic, and having formal fluidity, which liberated architectural geometry.

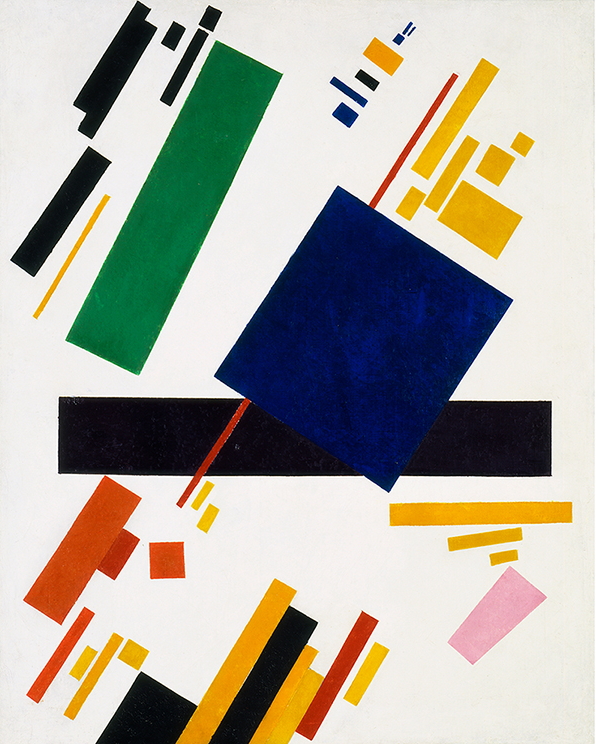

The origins of this, Schumacher said, can be traced all the way back to Russian painter Kazimir Malevich, who was considered a leading figure in geometric abstract art. Hadid was inspired by his work but also sought to build on it by layering more complexity in a bid to complete “unfinished modernity,” he explained.

Pillars of Inspiration

Schumacher’s lecture was peppered with what might at first appear to be oxymorons. He often described their approach to design with words like “scripted differentiation,” “principled variation,” and “complex variegated order.”

He labeled Hadid’s core pillars of inspiration “Zaha’s Radical Formal Innovations,” centering on four themes of explosion, calligraphy, distortion, and landscape analogy. Hadid’s chain of thought running through these concepts reflects her personal journey of challenging the existing order, while attempting to build a new one.

Her process of evolution begins with the notion of explosion, which looks to break up existing elements to open up a space for new interactions. She saw structures not as giant blocks that can only be placed in one mold or another, but as organisms with multiple parts that communicate with each other. The concept of calligraphy and doodles is what adds coherence to these elements. What to anyone else may look like a random tangle of lines on paper, provided Hadid with a way to visualize continuity in a structure and discover new spaces.

The result of this were designs that came with “perspectival distortions,” according to Schumacher. Having been stripped of rigidity stemming from straight lines and angles, the structures conveyed a sense of dynamism in the way they flowed. To some, they would look “skewed,” said Schumacher. This irregularity in shape also allowed the designs to be more adaptive to the surrounding landscape. Instead of having to cut into a slope to create a flat surface area for a single building, Hadid saw opportunities to tailor her design to the slopes not the other way around.

Hadid’s markedly different approach toward architecture produced breathtaking structures that leave onlookers with a sense of awe and fascination. The reason why so many think of her buildings as futuristic may simply be because they reflect a perspective so unfamiliar and refreshing in comparison to their current surroundings.

Parametricism Lives on

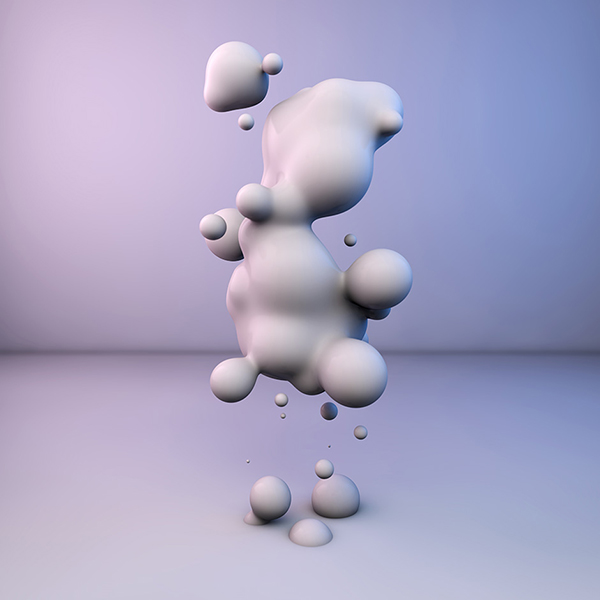

Years of designing and putting these foundational principles into practice eventually culminated in the birth of parametricism, coined by Schumacher in 2008. This represents the idea of using mathematical computations to attain complete fluidity in designs seen in Hadid’s work, which helps create an intricate order that cannot be drawn. Hadid once explained it was “an organic language of architecture, which allows us to integrate highly complex forms into a fluid and seamless whole.”

For Schumacher, this paradigm embodies the legacy of Hadid and will continue to be the vehicle for future projects. In his own words, it’s an “epochal” approach that signals a breakaway from the era of modernism, represented by rigid and closed shapes drawn with a “ruler and compass.”

With a ruler and compass, you can draw cubes, cylinders, and cones, but predefined geometric shapes come with limits. The principles of parametricism instead embrace fluid models such as blobs and pulsating surfaces. This variety gives structures the freedom they need to blend in with their surroundings. Schumacher explains, the fact that buildings can be designed to adapt to irregular shapes in the existing landscape is what makes parametricism a more logical approach.

This paradigm is also one that applies to both the interior and exterior of buildings, which any visitor who has stepped inside Hadid’s structures will have already experienced. The seamlessness seen inside the building means people have less visual clutter and one clean element to follow instead.

On a larger scale, parametricism calls for a collective identity in urban landscapes as well. A collage of random buildings with no rule of order, Schumacher said, results only in “garbage spill urbanization.”

Looking ahead, Zaha Hadid Architects still has dozens of projects that need to be completed.

The Central Bank of Iraq, the new Beijing airport terminal in Daxing, the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center in Saudi Arabia are just some of the major projects that have attracted much attention.

As recently as last month, ZHA won a masterplan competition for redeveloping the Port of Tallinn in Estonia, evidence that even in the absence of Hadid, her vision for synchronicity and connectivity will continue to live on in numerous parts of the world.