From 124 floors up on the observation deck of the Burj Khalifa, it feels like you can see for eternity. The desert city of Dubai sprawls below and the Persian Gulf fades into the horizon. But while marveling at the scenery, rarely do we think to marvel at the technology that makes such a view possible: the elevator.

It’s difficult to imagine that, at one time, the top floors of buildings were shabby attics used for storage and housing staff. Luxury apartments were on the first floors, favoring accessibility over scenic views. Advancements in elevator technology changed all of that, ushering in an era of penthouses and skyscrapers, and changing the skyline of every major city in the world.

Now a ubiquitous part of our daily lives in offices, hotels, and apartment buildings, the average person makes 250 elevator trips every year. The super-rich living in the top floors of some of the world’s highest residential buildings clock as much as 194 miles per year in the elevators just to get home. Suffice it to say, without the elevator, we’d all be stuck in the lobby.

The Beginnings of the Elevator

It might be hard to believe, but the first reference to an elevator comes from 236 BC in the writings of the Roman architect Vitruvius. He reported that the Greek mathematician Archimedes made a primitive elevator by hoisting ropes wound around a drum and was operated by a manpowered capstan.

Driven by the industrial revolution, the 1800s saw big advancements in elevator mechanics. The first major change was eliminating the need for manual operation. In 1823 two British architects, named Burton and Hormer, built a steam powered ascending room to take tourists up to a platform for views of London. Later innovations to their idea combined steam with a belt and a counterweight and became the new standard. But they had one major drawback: the cables could snap, sending the elevator plummeting, killing passengers or damaging the load on the way down.

Fear of falling several stories to an untimely death meant that most people were wisely wary of elevators. Elisha Otis, founder of the Otis Elevator Company, solved that problem in 1852 with the invention of the safety elevator. His system prevented the fall of the cab if the cables broke and is the foundation for modern elevator safety systems. With the public now more trusting of the technology came a new era of architecture and construction that fed off a desire to reach new heights.

An era of mega-tall skyscrapers began, and with it a need to engineer unique elevator solutions that could be incorporated into the designs of the buildings. In the last 20 years, Samsung C&T has incorporated new technology into their world-famous buildings around the globe.

Lobbies in the Sky

One of the major limitations architects faced in building mega-tall structures was that elevators could not reach more than 1700 feet. The hoist ropes became too heavy and were prone to snapping. To address this issue, the sky lobby was born.

Sky lobbies, as the name suggests, are an intermediate interchange floor where people can change from an express elevator that stops only at the sky lobby, to a local elevator which stops at every floor within a segment of the building. Though they were originally created due to technical limitations, they are also used to control the flow of traffic within a building.

The Petronas Towers, built by Samsung C&T, have one of the most famous sky lobbies in the world: the Sky Bridge. The towers are connected at the 41st and 42nd floor by a double decker bridge, which is the highest 2-story bridge in the world. While the lower floors of the building are serviced by two sets of six elevators, the Sky Bridge is served directly by five double-decker lifts. Once there, passengers take another lift to the upper zones.

Though the Sky Lobby sees most of the traffic for upper floors, another four dedicated executive lifts reserved for VIPS serve every floor. The executive lifts are the longest in any office building in Malaysia and can reach the top of the towers from the car park in 90 seconds.

The Need for Speed

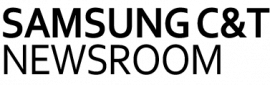

Construction of skyscrapers has always had a competitive edge, with architects looking to one up the competition with a few extra meters and stake their claim as the tallest. It’s also been rife with competition to see who can get to the top of their building the fastest, so taller buildings and faster elevators have evolved hand in hand. Samsung C&T’s Taipei 101 is a prime example.

At the time of its construction in 2004, it held the title of tallest building in the world and had the world’s fastest elevator. A Guinness World Record plaque hangs in the elevator lobby to make it official. Moving at 16.8m/s, Taipei 101 quickly earned the reputation for having the “Ferrari of elevator systems.”

Surprisingly, achieving the height and speed required for Taipei 101 was the easy part. The main challenge was making them run quiet. To reduce the noise – for both those in the elevator and in the building – the observation deck shuttles are shaped like twin-nosed bullets to reduce the aerodynamic drag, or what is known in the trade as windage. They are also equipped with sound isolation shrouds, acoustic tiles, and isolated floor platforms. Even the counter-weights had to be aerodynamic.

Up in the Clouds

Setting records has been a trend in Samsung C&T’s construction portfolio, and when they built the Burj Khalifa it was no different. When the building opened in 2010, not only was it the tallest building in the world, it held six other world records including one for the elevator with the longest travel distance, and another for the tallest service elevator. In total, the elevators cover 160 floors with the tallest elevator in the building servicing 140 floors.

But operating such complex elevator systems is no easy feat. The Burj Khalifa requires on-site technicians around the clock to keep the elevators running at peak efficiency. The system continuously monitors every aspect of the elevator’s performance and feeds information to displays in a control room monitored by the technicians. It’s a major change from the elevators of earlier skyscrapers like the Eiffel Tower and the Empire State building, which had relatively simple lift systems. Suffice it to say, we’ve come a long way from the days of Archimedes.